The Poetry Porch: Poetics

Twelve Questions:

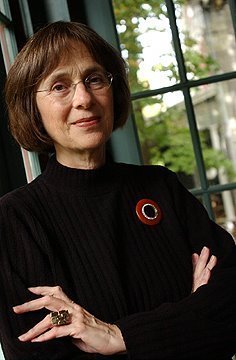

An Interview with Gail Mazur

In August 2012, Joyce Wilson conducted this interview via email with Gail Mazur on her life and art. Mazur is Distinguished Writer in Residence in Emerson College’s Writing, Literature and Publishing Program, and founding director of the Blacksmith House Poetry Center. See Gail's home page, and also the recent interview on the history of poetry at the Blacksmith House in Ploughshares, as well as an interview with Gail conducted by Lloyd Schwartz for PROVINCETOWN ARTS in 2008.

JW: Were you inspired by a particular type of elegy when you collected the poems for Figures in a Landscape? Approaching this book with the knowledge that it was published after the death of your husband, Michael, I had particular expectations about what I would find there. Yet the poems do not express a lament for the deceased so much as an affirmation of a life dedicated to art, the life you shared. Did you have a particular model for elegy in mind when you were putting this collection together?

GM: None of the poems were written after the death of my husband, but they were written in the terrible shadow of impending loss. Art, for me, for both of us, was what we believed in most profoundly, it was what our lives were about. While we were still together, the power of art, the intensity and frailties of love, and the fragility of life, informed everything. You’re right, it was affirmative. So, I wasn’t writing elegies. Not then.

JW: How did you meet Michael? Are your children writers and artists?

GM: We actually met when we were college students—he was doing his senior thesis, a book of woodcuts and wood engravings with Salome texts by Flaubert, Wilde and Mallarme, at Smith with the artist Leonard Baskin. Mike was a student at Amherst. I met him at the home of a classmate, Esta Smith, whose father owned a frame shop in Northampton and traded framing for art with artists in the area. We all went to see Clouzot’s The Wages of Fear, it was gripping, and I think we were in love before Yves Montand landed safely. We married within a few months, in the middle of my senior year.

My son, Dan, is a cartoonist and writer, and my daughter, Kathe is an actress. Mike always told them to do work they wouldn’t have to commute to in rush hour—so their options were limited!!!JW: I sense Michael’s presence in “A Small Door” and like the way the poem moves from place to thing to argument as the glue in a relationship. Is that him there in that poem? Also, is he the over-achiever in “Seven Sons”?

GM: Ah, no, “A Small Door” was written after the death of our friend, the sculptor Richard Rosenblum. We’d traveled to China together—Richard was a collector and scholar of Chinese scholar’s rocks, and we did go to Xian and saw the terra cotta army. He was ferociously engaged in, well, in everything, a brilliant contrarian. He died very young, and I wanted to get the sense he gave me both of engagement and a reassuring valedictory—the movement of the poem I hope reflects our travel, and his travels.

“Seven Sons” was really a poem that waited to be written from the time I was about ten years old, trying to understand the idea of sacrificing your life—or even more extreme your child’s life—for an abstraction, or a belief exemplified in what seemed to me incomprehensible: that it would be better to be slaughtered than to eat pork. And I already knew that the Dietary Laws were health laws, for instance that uncured pork could have caused trichinosis. My Jewish education was in a reform congregation. So, the idea that adult life was so severe, so terrible, that “someday” I would understand and perhaps make a similar decision. Brrrr. This is the poem to myself, not exactly my ten-year-old self, the child who grew up in a completely Christian community which had restrictions on what a Jewish child could belong to, who wanted desperately to understand the “history of the Jews” and the tribalism of religions.JW: Your later poems reflect continued care taken to structure, the nuts and bolts of having three parts, parallel to building an argument with thesis, antithesis, and synthesis. I saw this pattern in the poem “Hermit,” which discusses ancient Greece, the hermit crab, its habits and environs, and ends with the views about the hermetic life. Do you attribute a mastery of the traditional forms in rhetoric to your success with your later poems?

GM: I don’t know how to answer that question. I guess I don’t feel I’ll ever have mastered traditional forms—and when I do master something, I seem not to want to do it again. All the sequences I might dream of go unwritten!

With “Hermit,” there was an accretion of information that really came out of walking on the flats in Provincetown, reading about the hermit crab, and the peculiar phenomenon of the hermit crab’s shelter. As if it were an exemplar of the Freudian notion that the house/home is a metaphor for the mother’s body—the hermit crab enacts it, insists on it. And in fact, I had always wanted to write about (human) hermits, who aren’t like the crab, they don’t bring a companion in to share their houses. They disconnect their doorbells as if to say nobody’s home. So what I wanted to do was keep writing until I came to what that meant to me.

And then, of course, one shapes the poem the best one can. The order of that was a challenge, my page looked like a mathematician’s notes, a field of notes.JW: From the beginning, you practice a varied approach to metaphor, as if you are determined not to wear out the form. I sense, from the beginning, that you have an aversion for, or at least a wariness about, the simile. For example, in “Baseball” from your first collection Nightfire the first line begins, “The game of baseball is not a metaphor,” exploring all the things it is not so that you can conclude with what it is. In “After the Storm, August,” from The Common, you ask “What can I learn from the hummingbird,” which frees you to render the bird’s identity through contrast with your own, without relying on the words “like” or “as”. In your most recent work, “Enormously Sad,” the poet asks, “Compared to what?” as it introduces an inquiry into the emotional state of sadness. Even “Zeppo’s First Wife” describes its subject in terms of the stages of familial relation, “unremembered distant half cousin nonce removed” in lieu of giving stages of a relevant biography of the woman. Is there an underlying logic in your approach to comparing unlike things?

GM: Well, of course, baseball, to the ardent fan, IS a metaphor and more. I couldn’t write that poem until I thought of denying baseball was a metaphor, then I could go all out. Everything about the game and the park seemed like metaphor. And a fan’s sense of loss—or exhilaration—no matter how intense, is more bearable than the real losses in our lives. But still, but still, one feels one lives and dies, as the saying goes, with one’s team! After the first line, I wrote it in a few minutes, one of those gifts.

I have come to the point where the questions I ask myself are part of the poem, and unanswered. “Compared to what?“ I challenge all my assumptions; it’s amazing I get anything done.

I suppose it’s really just the way my mind works, a constant argument with the self. And with Zeppo’s first wife, my putative relative, it seemed at the time I finished the poem, impossible to find any “relevant” biographical information. I didn’t know—I still don’t—how we were related. But I was really trying to write a poem against dismissing “insignificant” lives. (Provoked a little by friends who were Yankees fans mocking me for finding my team, the Red Sox, interesting and wonderful to follow-they WERE! They are!) Zeppo’s story, the Zed, the straight-man, the least of the Marx brothers, illustrated that for me: he was an inventor! What he invented was shocking! He was “the funniest” of them, yet never permitted to be funny. And really, all of our stories are interesting, depending on how they’re told—and isn’t that what writing is for, too?JW: I admire the way many of your poems are long, filled with details and a sense of completion. How have you resisted the pressure to write short poems?

GM: I haven’t felt the pressure to write long, or short, poems. Sometimes I’m writing a short poem but it just won’t stop, and then, of course, it isn’t the poem I thought I was writing, it’s a surprise. Surprise is the greatest gift in the process, it comes mysteriously out of the process. Sometimes the poems just keep pulling me, won’t let me stop. I’d like to thank them for not quitting on me!

JW: Often the wisdom in your poems comes from a quotation from your mother: “Oh no, Gail,/ the rose doesn’t come/ to you—/you go/ to the rose“ (“Dana Street, December”). Do I also sense a distillation of Hebrew scripture (about penitence, atonement)? The stanzas in “Five Poems Entitled ‘Questions’” seem almost inspired by Buddhism. Or were they? The mind of the child, the awareness of the body, the need to speak, to practice goodness, to be penitent—all of these are quite universal, yet particular to your own vocabulary. Where do you derive your sources of wisdom for your poems? Do you begin with these insights of wisdom or with details?

GM: Ha! That wasn’t my mother, it was Stanley Kunitz, who was a great gardener!

JW: Oh, thank you; however, the lines, “I don’t want/ a bird, I want a blue egg” (“Evening”), are from your mother?

GM: Yes! I think I am almost always beginning with details, but never with “wisdom.” (Or beginning with a phrase, a sense of music, a line that is going nowhere until I write it and it goes to another line—) I like to feel the poem is thinking its way along, making associative leaps, cannibalizing what I read—which is so various—and questioning the consolations and assumptions of, say, scripture, Buddhism, psychoanalytic thinking.

The question of “goodness,” of what it is to “be good,” of self-consciousness—that’s nagged at me since I was a child.JW? Who was your favorite poet when you began writing? Which poet—perhaps it was more than one—has influenced you the most?

GM: I’m not sure when I did begin. But the first poems I memorized were Dylan Thomas’. After some Shakespeare sonnets. Early on, Lowell may have been the strongest influence. Then, then one devours poetry and I couldn’t begin to list the poems that have taught me what I felt I needed. 20th century: O’Hara. Bishop. Milosz. Pessoa. Donne. The Romantic poets. I think now so much in terms of individual poems—that’s what is so satisfying about keeping a “favorite poem” file. The poems of my closest friends, and their responses to my poems, are incredibly important to me now.

JW: I am aware that you have studied the work of Elizabeth Bishop and Robert Lowell. Do you have any thoughts about the ascendance of the poetry of Elizabeth Bishop and the current distaste for the poetry of Robert Lowell?

GM: Well, there have been so many cultural changes. The ascendance, as you put it, of Bishop delights me. Lowell is harder for people, very hard for my students, but I’m sure his great poems will last as long as anyone’s. When I teach them, my students do become enthusiastic. And of course, I can walk them up to the Shaw monument across from the State House and read “For the Union Dead.” Even with tour buses and horns honking, it’s thrilling. There’s most often a lessening of interest after a poet’s death—except in the case of dramatic deaths, I suppose—In the arts, there’s always the possibility of rediscovery.

Maybe in some way, most of the information in Lowell’s poems, the enormous scope of history which is so central to his view, is like Greek to a 22-year old American aspiring poet. I like to give them some information while we’re reading, so history itself is essential, not a series of stumbling blocks.

And finally, in many of the sonnets of Notebooks, History, The Dolphin, he’s an elegiac poet. He’s a poet whose energy and metamorphoses they can read their way through. He’s not “cool”; sometimes young poets try hard to be cool. He’s a brave, tragic poet, there will always be a lot to learn from his work.JW: Some of your poems have been closely inspired by the Italian poet Vittorio Sereni and Catullus. Have you translated the work of these poets or just imitated them? Do you plan to embark on a translation project in the future?

GM: I’ve done both, but right now I have no plans. Michael was fluent in Italian and he could help me, particularly with the sound of the original poems. My favorite translation I’ve done is of Michelangelo’s tailed sonnet written while he was painting the vault of the Sistine Chapel. It’s one of my favorite poems, much translated, but in my searching I never found a terrific translation, It’s fresh, passionate, desperate, brilliant in the Italian and even in some of the stilted translations I’ve read.

JW: Do you sense that the students of poetry today have changing tastes, changing aspirations? How do you assess the future of teaching poetry, the MFA in creative writing?

GM: Oh, everything changes, the role of writing programs has exploded—not imploded—in the last 20 years, writing programs have become a huge academic subculture.

If there’s a change it’s from the compulsion of a vocation to the notion of a career. What we try to give them is honesty, respect for the history of the art, respect for what Elizabeth Bishop said she admired most in a poem—accuracy, spontaneity, and mystery—and the importance of craft no matter what they come to graduate school thinking about form.

Some of my friends say their students only read each other, but I find that my best students are great readers and not only of their contemporaries. None of it is wasted, you hope that they’ll move into their lives loving poetry, being fed by it, reading it, sharing it, teaching it, whether or not they continue to write poems. The performing of poetry has become a big part of their culture. What does that mean? Probably it gives the little-published poets a way of “publishing”; I hope it means more musicality in the work.

But students should know the MFA earned is the beginning of a life of tightrope walking without a net!

Return to the beginning.

Return to Poetics. Return to the Poetry Porch homepage.

Send comments via email to Poetry Porch Mail.