Return

to Warsaw

by Helen Degen Cohen

Majka (pronounced Mayka), modern

as a young Shelley Winters, is trying to be patient with her overly religious

Catholic mother. The mother who is looking at me with those same eyes—though

not as deep, not as foggy any longer—as she did when I was eight years

old, when she had me in hiding among the wheat fields. She is eighty-five

years old now, sitting in a house dress that covers her sagging weight,

her bad legs. Her gray hair is brushed back into a bun, and deep in her

still smooth face, her eyes twinkle. She is staring at me with a slight

smile. Mocking? Scrutinizing? Without any loss to her dignity, hands quietly

in her lap, like a Mona Lisa. She is asking me questions, though not the

ones I would have expected. She is entirely flesh-and-blood now. No. Not

entirely.

If Maria Szumska

were entirely of this world now, her daughter would not be so impatient.

It’s a habit, the way Majka reacts to her mother, to everything her mother

says. She shifts in the chair, flushes, perspires. As if to say, oh please,

they know already, why don’t you leave them alone. And yet she is

her mother’s daughter. She herself has just made a pilgrimage, to Wilno

(pronounced Vilno), as I am making mine, to Poland. Majka knows that this

is my pilgrimage, she has made every conceivable accommodation for us,

but this is her mother, this babcia (bahb-cha—granny) who will not

leave the little three-room apartment on the fourth floor, who insists

on sitting in the corner of the room—where she literally lives, eats, sleeps,

watches television, and writes letters to missionaries. If Maria Szumska

were entirely of this world now, her daughter would not be so impatient.

It’s a habit, the way Majka reacts to her mother, to everything her mother

says. She shifts in the chair, flushes, perspires. As if to say, oh please,

they know already, why don’t you leave them alone. And yet she is

her mother’s daughter. She herself has just made a pilgrimage, to Wilno

(pronounced Vilno), as I am making mine, to Poland. Majka knows that this

is my pilgrimage, she has made every conceivable accommodation for us,

but this is her mother, this babcia (bahb-cha—granny) who will not

leave the little three-room apartment on the fourth floor, who insists

on sitting in the corner of the room—where she literally lives, eats, sleeps,

watches television, and writes letters to missionaries.

Maria Szumska sits at her

table facing the window (and me, now), writing meticulous letters in a

nearly perfect hand. The hand was perfect a year ago, but now it is less

steady, the lines don’t run as neatly across, nor do the letters stand

as regally. But God forgives what can’t be helped. Her stationery is precious.

I know it so well. It has a red rose on each sheet. (There are huge red

roses on a dark gray tapestry on the dining room wall, roses the size of

lions. She has kept that tapestry since her youth in Wilno.) She addresses

the envelopes just as carefully, an ingrained European habit, developed

when correspondence was a matter of life and death, when packages and letters

carried, or asked for, vital help or information, when telephones rang

only in the movies. Written communications in Europe are still precious.

Addresses are precious. When after the war my mother wanted to bring her

family to America, she had to recall the address of an uncle in Chicago.

There were four digits in the street number, and try as she might, she

couldn’t get them quite right, until one day she was close enough, the

letter was somehow delivered and––that is why I am here today. When I’m

in Florida I see my mother addressing packages to Israel, to Iowa, to Poland,

I see how carefully she prints each name, every digit.

The table is up against

the window. Maria Szumska sits facing the gray buildings of the suburb

Ursus in the window, pen in hand. A few feet to her left, nearly touching

the swung-open window-frame, is the television set, and on its screen the

politics of Poland. She is writing a letter to a missionary and watching

the changing fate of Poland, as we come in.

Maria Szumska is a super-patriot.

She is passionately involved in what happens on the television screen.

It is a gray meeting of the government officials, in a huge hollow assembly

hall. It lacks the spunk, the showmanship, the confrontations, the play,

of U.S. hearings on television. This meeting is dead serious, the room

seems gigantic, the men lost within it, talking in gray, somber voices.

It goes on and on for hours. She doesn’t take her eyes off it. Her daughter

Majka is extremely annoyed.

“You can finish later,”

she tells her mother and shuts off the television set. Maria Szumska acquiesces.

She begins to talk about Poland, about its patriots, its martyrs, one after

another. She pulls out pictures of saintly heroes, of Holy Mary, of the

Pope. They seem to appear out of nowhere, since there are no files to be

seen. They are postcard-sized, most of them, depicting heads with sharply

pointed haloes. She is not senile, she repeats herself out of her intense

preoccupation, repeats stories of her heroes day after day, which I still

can’t absorb fast enough—I am still getting re-acquainted with the language.

I try, I bring tapes, I hang on every word. I want to listen with everything

I’ve got. This is my pilgrimage, after all.

On the table are a bowl

of red currants, bread and sausage, a vase of flowers. Majka brings meals

to her mother two or three times a day. And now that Majka has left us

for a bit, her mother leans forward to ask me a favor, a secret. She wants

to know if I could get her some milk chocolate. She accents the milk.

Milk

chocolate. But don’t tell Majka, she would get angry. I say of course,

looking around. I am always looking around, as if she were made of the

room itself. My back is to the window, and I’m looking into the room, at

her bed along the wall on my right, at the picture of the Madonna high

on the wall, beyond the television set. Szumska is facing me, to my left,

penetrating me with her stare. It is not a spiritual stare, as I expected.

It is a worldly (bemused?) stare.

She has just talked about

the glory of Poland, and now she stares at my American athletic shoes.

Nods with approval. Her granddaughters should have such shoes. Majka comes

in at that point and her face goes red. I wish it didn’t amuse me as it

does, this trip was supposed to be all sacred.

When I was almost eight

years old, we stood at a train station in Lida, my parents and I, about

to be shipped to the camps. My mother gave me a cup and told me to pretend

I was going for water at the pump––and to keep on walking until I found

the house of a woman we knew. I asked for directions from house to house.

I walked across the town until I found the woman’s house. But because it

was too dangerous for this woman to take me into hiding, she searched for

someone else, and found Maria Szumska.

It is a much longer story,

of course. The woman my mother told me to find was a cook at the town prison,

where we had been hiding in a room over the guard house, my mother, my

father, and I. Because my father had made himself indispensable at the

prison (by barbering, distributing food supplies, and supervising all the

plumbing), he was permitted to move us from the ghetto––where living conditions

were miserable and hundreds of thousands of people were marched into the

fields to be shot during “selections”––to live, discreetly, at the prison.

In the end, though, we too were rounded up, with the rest of the remaining

Jews in town, and placed on trucks headed for the train station and the

camps. That is when my mother handed me the cup and told me to find the

prison cook, Waclawska (Vahtzlavska). When I was out of sight, she and

my father boarded the train and later joined an escape party: while the

train was speeding, they had a small boy squeeze out of a tiny window and

unlatch the door from the outside; whereupon eleven people (out of five

hundred) jumped, four were shot immediately, and seven survived and joined

the underground––my parents among them.

After several failed efforts

at finding me a safe place with someone else and having appealed to the

Mother of God, Szumska decided to do it herself. She sold her clothes,

and with the money rented a cabin in the country. She was an educated,

striking young woman, and her clothes too must have been attractive. Before

the war her husband loved taking pictures of her, one of which is now displayed

on the wall––a picture of a beautiful, dark-haired young woman seated on

a lawn, her romantically ruffled white dress spread out around her.

Maria Szumska left her husband

in Lida and came to live with me in the country. She would walk twenty-five

kilometers from our cabin in the country back into town, to do her husband’s

laundry and get food to him. It occurs to me that I still don’t know how

she got all our food, even after all the questions I’ve asked her. We picked

some of it wild, like spinach and chamomile and stray carrots, and poziomki––tiny

wild strawberries. (Truskavki is the word for normal strawberries;

these tiny ones are poziomki.) She made potato dumplings which we

ate in hot milk with boiled carrots. She baked some of our bread herself,

in a make-shift oven. She walked me to the forest and lake. She left me

with what I call “the cousins” in a novel I have written about the war,

though now it seems that they may have been “neighbors.” They were farmers,

I am almost sure of that. That was in 1943.

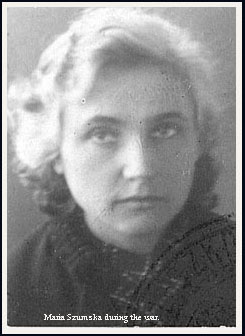

Szumska was in her thirties

then, with prematurely milk-white hair––it had turned suddenly white soon

after that romantic picture on the wall––and a pure, doll-like porcelain

face with haunting eyes––liquid, moonstruck eyes, as I remember. In the

pictures she shows me now they are sad, melancholy; to me, then, they were

only mysterious, only other-worldly. I have moved onto the chair on her

left, shoulder to shoulder, and she turns to look at me more closely, and

tells me that my teeth could be whiter. The surprise that goes through

me amuses me––I am disconcerted, I accept everything. I look straight through

her, into her, trying to see the young woman, the one who sleepwalked and

prayed, prayed and sleepwalked, who crossed her hands on her chest beside

me, when we lay down to sleep, in the cabin in the country. The young woman

who showed me a world my parents never knew, though they survived the war

and are alive1 and well

in Florida.

***

What else did we do in Poland in July?

We toured Warsaw; we were taken to both northern and southern Poland. Majka

and her husband Jacek (Yahtzek)2

had met us at the airport and brought us to the house they were building

out of concrete. They put us up in an upstairs room which belongs to their

then nineteen-year-old daughter, Dorota, since both daughters (the other

was twelve) were staying at their rented cabin in the northern country

(“on the Mazurkas”). Several days later we took the opportunity to get

into that northern vacation countryside by accompanying Jacek on his trip

to pick up the girls at the cabin and bring them home (at which point Dorota

would share a room with someone else and continue to let us use her room).

It was our first trip out of Warsaw.

Jacek drove us there in

his fifteen-year-old Mercedes. We reached our destination, near the Russian

border, hours later. (Lida and the cabin where Szumska had had me in hiding

were just across the border, but we had no Russian visas with us). It appeared

to us a primitive, somewhat depressed country, and their cabin was a shack;

but the girls loved it, it was summer camp, it was freedom to them. They’d

become housekeepers, were perfect hostesses when we arrived, cooked meat

and potatoes and made us tea. We picked wild strawberries and blueberries

in the forest.

***

In my book we are

spirits, Szumska and I; in July of 1989 we are encased in concrete. Literally.

We are seated in one of the many gray concrete buildings in a suburb of

Warsaw. They don’t have the paint with which to cover the dirty-looking

ugliness of concrete. When you land, the entire city looks gray. When you

land, you smell the odor of war. I am not exaggerating. We looked out the

windows, as the plane rolled in, and saw several Russian military men in

green capes strolling around the bleak airport, the flat overcast gray

city behind them. Outside, my friend asked me, “What is that odor?” I said,

“It’s the odor of war.” Months later, in a book on Poland, I found that

another writer had characterized it exactly the same way. My friend wondered,

later in our trip: “What did they do with the rubble?” We had just finished

seeing a film on the demolition of Warsaw by Hitler. It was shown in an

upstairs room of a museum, with the windows wide open, overlooking the

rebuilt Old City square, painted in colorful pastel shades, with tourists

and artists wandering around below in the heat, or sitting under ice-cream

table umbrellas. The scene below us, through the wide-opened windows, was

in such contrast to the crumbling, black-and-white Warsaw on the screen,

that I think we both wondered: what happened to the rubble? In my book we are

spirits, Szumska and I; in July of 1989 we are encased in concrete. Literally.

We are seated in one of the many gray concrete buildings in a suburb of

Warsaw. They don’t have the paint with which to cover the dirty-looking

ugliness of concrete. When you land, the entire city looks gray. When you

land, you smell the odor of war. I am not exaggerating. We looked out the

windows, as the plane rolled in, and saw several Russian military men in

green capes strolling around the bleak airport, the flat overcast gray

city behind them. Outside, my friend asked me, “What is that odor?” I said,

“It’s the odor of war.” Months later, in a book on Poland, I found that

another writer had characterized it exactly the same way. My friend wondered,

later in our trip: “What did they do with the rubble?” We had just finished

seeing a film on the demolition of Warsaw by Hitler. It was shown in an

upstairs room of a museum, with the windows wide open, overlooking the

rebuilt Old City square, painted in colorful pastel shades, with tourists

and artists wandering around below in the heat, or sitting under ice-cream

table umbrellas. The scene below us, through the wide-opened windows, was

in such contrast to the crumbling, black-and-white Warsaw on the screen,

that I think we both wondered: what happened to the rubble?

It must have been recycled.

It smelled to me––initially, at least––like recycled war. And yet when

we got into it, the ordinary life of the city made us forget the smell,

all our initial impressions, just a week into our stay. By the time we

left Poland, two weeks later, we’d forgotten it entirely. You can imagine

what happens to permanent residents.

***

In The Book of Laughter and Forgetting, Kundera says that “the struggle

of man against power is the struggle of memory against forgetting.” But

it seemed that the struggle in Warsaw was in both directions––to forget

on the one hand, and not to forget on the other. To forget––in the form

of building new houses, questing for jobs, American shoes, rock music.

To not forget––in the form of Jacek, as he stood in back of his house looking

around at all the land that once belonged to his family; of Szumska, reviewing

her pictures; of Majka, making her pilgrimage to Wilno, when it was finally

allowed, in May of 1989. Many such freedoms are only a few months old,

in July of 1989. What was the black market currency exchange rate only

three or four months ago is now the legal rate at any of a number of public

currency exchanges. Once can choose whether to buy meat at a state-run

store, or at a private booth at the market. Women in babushkas sit on the

sidewalks of Warsaw selling raspberries. There are long lines at the “dollar”

stores––where one can use dollars or marks only––for Western goods. Everything

is all mixed up. In July 1989, it is practically impossible to forget,

though there is little time to remember.

The ghosts of Jews are everywhere,

though I realized it only gradually. One begins to forget the odor in the

air; one begins to remember the Jews, in time. It’s a story I don’t want

to get into here; not at this time. It is too big, too complex. But what

is curious is that the more the Jews dwindle here, the more their ghosts

are felt. Poland is a country dotted everywhere with death camps, and yet

people live all the way up to their edges––new and old developments are

immediately adjacent, children play along their fences––without acknowledging

them. Jacek had never been to Auschwitz and didn’t want to go with us at

first. “It is too macabre,” he said. Though he did decide to go in the

end, even shed some tears, and was glad for it. Majka had been, before.

I didn’t cry at all. I wanted to write the story of the tour guide, a Polish

native of Auschwitz (Oswiecim) who as a child had been exiled with his

family from his town, while they were building the camp. He returned in

middle age, to do tours of the camp––every day, day after day, year after

year. “Six million Polish citizens died here,” he says, day after day.

“Three million of them were Jews.”

The Jews and the Gentiles

had lived like two countries intertwined, co-dependent as Siamese twins.

Three-quarters of the world’s Jews once lived in Poland. There were 3.5

million at the start of the war, about one tenth after the war, and only

5,000 by the mid-1980s. Two post-war occurrences, one of them a pogrom

in 1946, and the other a government-encouraged wave of anti-Semitism in

1968, account for the two mass emigration of Jews from Poland. I had never

known this. No one I’ve asked since knew anything about it. When I returned

home, I read it in a book called Remnants3,

given to me three years earlier by a Catholic ex-nun. Strange, that I haven’t

read the text till now. It is in a way a history of my people. It interviews

a handful of the handful of remaining Jews in Poland, most of whom are

old or sick. I picked up other books, with similar accounts. There is much

more I have to read.

Majka and Jacek drove us

south to Krakow during the second week of our stay, and there, at a museum

across the road from our hotel, advertised in bold letters, was the exhibit

“ZYDZI––POLSCY” (“The Jews––of Poland”), paintings of Jews and their life

in Poland, predominantly portraits from centuries past, young and old,

some with flowing Jesus-like hair. From the book Zydzi––Polscy which

accompanies the exhibit: “. . . the few thousand Jews still living in Poland

can by no means carry on life in the social structure which belonged to

their fathers and grandfathers. A thriving graft has been cut off; its

oral transmission has been reduced to single stereotyped phrases. . . .

Those of us who are quick to blame others, including Jews, for our misfortunes,

and who worship our poets and artists, will be reminded by the exhibition

of how high a regard for the Jews those poets and artists had. The Jews

in turn, historically made sensitive to everything that concerns them,

will sense sympathy and even admiration in the works of Polish painters,

the artists of a nation at whose hands they have suffered in the past.”

The few people in the museum were staring at depictions of a vanished culture.

It was haunting, as are the suppressed attitudes towards Jews.

After dinner, back on the

third floor of the Hotel Cracovia, I heard some singing, in Hebrew––songs

I had known in West Germany after the war, at a D. P. camp, where our common

language had been Hebrew. The sound was incongruous with the setting. This

was Krakow, 1989. I had been an impressionable kid, I had loved those songs

and dances. I followed the sound down the hallway, toward our third floor

lobby, where I found a group of high school students from Israel, singing.

I asked if I could join them, and two girls made room between them on a

couch. They weren’t just singing, they were making a statement: it was

blatantly exuberant singing. They were laughing, singing, clapping. It

was their version of “We Shall Overcome.” The director said they were here

studying the camps (Krakow is near Auschwitz), that otherwise they wouldn’t

know anything about them.

Upon my return to the U.S.,

I was told by a Pole who has lived here several years now that people on

buses in Warsaw, as well as Polish cleaning women in the U.S., are still

overheard saying, “It’s a good thing Hitler took care of the Jewish problem.”

When Majka took us to Grójec, the town where I was born, just south

of Warsaw (a thriving “shtell” pre-war, like the one in Fiddler on the

Roof, but now a rough-looking place) and asked, at a tiny tourist office,

whether there are any Jews left in Grójec, she was told that yes,

there are a few, but they wouldn’t own up to it. The famous Warsaw Ghetto

(famous for its uprising against Hitler) is a large square, empty park

surrounded by apartment buildings. Where so much had happened, there was

nothing, not even visitors. We were the only ones there, standing before

the monument to the heroes of the uprising, the ghostly emptiness palpable

around us. The neighborhood where my father had been born was nearby.

The subject is overwhelming,

and I am open. All my pages are open. I don’t want to write on the white

till I know what to say. I was in Poland in July, 1989, to see, to ask

questions of, the woman who had risked her life for my sake. She is Polish,

and Catholic.

There I stand, overwhelmed

in the indoor tourist market, Sukiennica, trying to buy Babcia a present.

Strange that we call her Babcia, or Granny, the woman who once haunted

the countryside like a saint. What can I buy her? We can’t find slippers.

We can’t find chocolate. And besides, I want to get her something meaningful.

I’ve come all the way to Poland and I can’t give her anything. What would

you give her? A Polish doll? A Polish wooden plate? A necklace of amber

beads? And then I see some plaques, upon which are painted madonnas. They

are cheap. Too cheap. But what else in the world can I give her?

She is disappointed that

I haven’t converted. My son married a gentile. She asks me––did he convert?

No, I tell her. She looks at me. It is a great surprise to me, the greatest

surprise of the trip––that she’d wanted me to convert back then. She had

asked the priest, and he had told her to wait, that perhaps my parents

would return. I always thought it had been her idea. That she was all spirit,

all noble. She is smiling at me. Her eyes twinkle. There is dignity in

the way she is sitting. I feel thankful, in a way. I feel peaceful. Everything

is as it should be, in a way. I love her, in a way.

This is not the spiritual

trip I thought it would be. This is an earthy trip. It is loaded with raspberries,

sour cherries, black and red currants, strawberries, tomatoes such as we

remember in dreams; home-made sausage and fresh white cheese for breakfast,

along with a platter of sliced cucumbers, onions, and tomatoes, four kinds

of bread and sweet rolls. We have ice cream at mid-morning almost every

day on our jaunts to Warsaw, we look into every window for amber, the streets

are full of ordinary people. I see nothing especially spiritual, no one

straining to remember or forget. The crowds are in the streets as they

are in Chicago, impersonal, shopping. They look Western. What can I bring

back to Szumska?

Her daughter, Majka, is

our hostess, our joy. Working at the sink in her modern kitchen, she turns

to smile at us. Warm, demonstrative, motherly, with plenty of flesh on

her, and blood that keeps rushing to her face, she cooks for us day and

night, like crazy. Cakes and “ushki” (fried pierogi, or dumplings,

stuffed with mushrooms), and soups, and cutlets and borscht, and potatoes.

There’s fresh berry juice instead of water (which she boils). The only

thing they can’t give us––anywhere––is ice. It’s strange all right, to

have nothing cold, no Coca Cola (which is served everywhere, but warm,

in lieu of water), no beer, not even cold ice cream (nearly all melted

and topped with berries), nothing cold whatsoever, but then what is ice?

Majka drives us everywhere, she won’t let us out of her sight, afraid that

we may be treated rudely, be cheated, be––who knows what. We see palatial

Lazienki Park with its roses, sculptures, and princely buildings. Churches,

cathedrals. We take us all out to a restaurant and can’t spend more than

a dollar. And throughout it all, Babcia is sitting at her table, with her

pen, indelible.

Behind the concrete house

they’ve been building for three years, Jacek’s brother Mihal has his greenhouses

and his outdoor flower and vegetable nurseries. Behind them is Babcia’s

apartment building, rising gray, with its flower boxes. We cut through

the planted field each day to visit her, passing Mihal’s wife Yola in the

field. We enter the bleak elevator building, ride the rickety elevator

up, and find Babcia in precisely the same spot, at her table by the window,

the television set on her left. She turns toward us, slowly, happily, waiting

for me to hug her. There’s a Friday in each month when a priest comes to

see her for a private mass.

I take out my present, loosely

wrapped in paper. It is from Krakow, I tell her. She didn’t want us to

go to Krakow. It was too hot, and she was afraid for Jacek, with his bad

heart. She looks at the present suspiciously. Oh, it costs too much, she

says, without having seen it. She smiles uneasily. I unwrap it. She stares

at my plaque with the painted Madonna. What do I need it for, she says,

I have one already. We both look at the Madonna on the wall, and I feel

my embarrassment, my inadequacy. She looks at the present again, kindly.

I thank you very much, she says, but you take it. Here it will be soiled.

Not quite “soiled”––the word is untranslatable. It will be damaged, disrespected,

trashed. I know what she means. Halinko, she says to me, my life is an

infinitesimal minute. I am gone. This must not be soiled. Take it. She

hands it to me. I don’t know what to do.

She stands up laboriously,

walks toward a drawer, and extracts several more items. A gray, tinny cross

on a chain. Some dresser covers, which she herself had crocheted, years

ago. Hand-crocheted doilies in several sizes. She returns laboriously to

her chair and places the items neatly before me.

By the time I have returned

I will have a half a dozen books, a peasant skirt, earthenware bowls, holy

pictures and objects, home-made jams and dried mushrooms, vodka, and of

course all the store items: dolls, garlands, beads, wooden plates––folk

art sold at the state-run Cepelia stores. Most of the presents will have

come from Majka, one of the books from Mihal and Yola. It is Pan Tadeush,

Poland’s most beloved book of poems. A large, hard-cover book, it must

have cost them a pretty penny. Mihal has been treating us to vodka in the

back yard adjoining his flower nurseries, amidst sunshine and roses growing

among the weeds. Yola has baked a cake for us, brought me flowers.

Flowers and berries are

dirt cheap around Warsaw. When it comes to roses, I have never seen so

many in my life. They seem to grow like weeds, among the unmowed grass

along the sidewalks, behind fences, in the parks. Lazienki Park has square,

formal gardens of the same red roses as far as the eye can see. The king

had his mistresses and bath-houses there, and an outdoor theater, now in

ruins. On one side of the river lived the royalty, on the other was the

poor (then Jewish) neighborhood, with its huge outdoor market, still there.

When we come home from sightseeing, a friend of the family, a stranger,

greets us with flowers, for me––for my name day. We were met at the airport

with flowers and sent home with flowers.

In 1943, when I was in hiding,

I lived intimately with a wheatfield, and even more intimately with habri

(hah-bree,

plural for “haber”)––what we call here the cornflower. But there, beside

the floppy orange poppies, the fragrant blue cornflower is radiant. I wish

we had a different name for it, since in Poland it grows along the wheatfields,

not cornfields. I’ve never seen a cornfield in Poland.

Habri are

on Polish postal stamps. Habri are my madeleine, the intoxicating

whiff of my year with Szumska4.

Pansies are the whiff of

my earlier childhood, when I could formulate no thoughts about pansies.

Or sunshine. Or wars. Habri have become more generic, are the sun

and the moon turned into a flower, the sum of everything I’ve named beautiful.

I was dazzled, while in

hiding with Szumska. And mystified. I’d been lifted out of the heat of

the war and set down in a wheatfield––where the sun was cool as glass and

the Holy Family lived with us in the dark cabin. Seeing that I liked to

sketch, especially when she left me alone at night, she bought me a pencil

for my birthday. It’s the most important present I have ever received.

One pencil. Would the soul be happier with twenty? Never. The soul is happiest

when it isn’t abandoned. The pencil was and is my surrogate mother and

father.

She brought branches into

the cabin and stuck them in the ceiling, for decorations. We brought in

wildflowers and placed them on plates on the floor, as decorations. She

brought in a fir tree for Christmas, and I made paper chains, angels, Saint

Nicholases and stars. When on one occasion she left me with the “cousins,”

Nazis came in to interrogate the family, and me too––since they’d heard

a rumor of a Jewish child in the vicinity. When one of them came up to

me and asked me, “Are you Jewish,” I was dumb. The farmers were so genuinely

stunned that the Nazis had to believe them, give up their search, and leave.

How could anyone ask such a question of a child, of Szumska’s niece, Szumska,

who was holy? At least that’s the way I remember it.

I am trying to leave a hundred-dollar-bill

for her. She protests, mildly, glancing at Majka. Majka is beet red. No,

she says. And to me, You have brought enough, we have enough. But it’s

for her, I tell her, in case something goes wrong, and you need

it. We can take care of her, says Majka. While her mother begins to calculate,

Well, the pension comes to . . . Majka is livid. Don’t take it! she orders.

I know what a hundred dollars means. One dollar is 5,000 zlotys,

a large head of cabbage at the city market is 100 zlotys. A pound of meat

at the state-run store is 1,000 zlotys; at a private stall in the

outdoor market, 6,000 zlotys. We bought the girls Puma athletic

shoes, and Agatka slept in them all night.

It has occurred to me to

wonder who has the richer life, Majka or her mother. Majka, with her busy

suburban household, with her husband (Jacek’s workshop in is his house)

and their workers, the children and their friends, Mihal and Yola, guests

and neighbors. Maria Szumska, alone in her room, her mind flooded with

the distant work of missionaries, the entire kingdom of the Holy Family,

the nobility of Poland’s heroes. What makes Maria Szumska unique is the

largeness of the world within her mind. Were she to be moved into her daughter’s

house, the noise would disturb her world. The sorrow she feels toward her

daughter’s lack of the spiritual is matched only by Majka’s sorrow. And

yet their names are the same: Maria. Majka is a nickname. And I felt like

a bridge between them. We’ve all suffered and tried.

Even the suburb at first

seemed drenched in the worn-out odor of its history. It came in the open

window of our room––Dorota’s upstairs bedroom. The bodies, the buildings,

the manikins in the windows, the ghettoes and castles. The walls. It’s

not like your normal industrial smog, said my friend. We were silent. Majka’s

friendly voice intruded. The trees intruded, the forest was unreal. Each

time we drove into Warsaw, it seemed hotter. We noticed the strangeness

less, and the shoppers and the heat more. Trying to find parking. The lines

for vodka and meat. Communist government buildings, street names. People

(quiet people, speaking in undertones), an underground of people,

sidewalks full of people, museums, Stare Miasto (Old City), lody

(lawd-y, ice cream); hushed, harassed waitresses. People in a corner of

a square, along a wall, hushed in the strange light. In one upstairs room,

a film about the destruction of Warsaw. Clips of survivors wandering among

the ruins, looking into the holes of the city.

These people could never

be American, much as they would like to be. Nowoczestno. Modern.

Be Nowoczestno, and come work for us, says a sign on a state-owned

streetcar. It seems to be moving through a fog, to our left and behind

us, as we ride in Jacek’s car, as if it’ll never catch up. It passes us,

into a new fog.

Dziecinko (my child),

says Babcia Maria Szumska to me, we must be thankful for what God has given

us. She points to the features on her face, saying, The mouth speaks,

the eyes see, the ears hear. Often she complains about how difficult

times are, how empty the stores are, echoed by Majka. She goes through

her litany of sighs, how weak she is getting, how much she has lived through,

how difficult it is to die. Then her face changes, she wants me to buy

the books of a missionary, to contact certain people in the States, to

repeat after her: The mouth speaks, the eyes see, the ears hear.

What more can we ask for, Dziecinko?

***

This wasn’t a spiritual

journey. Nor was it a temporal journey. It was a door I have walked through.

Everything begins here. There’s a weight to it. It’s as if I’ve built my

own concrete house and then walked through it––in the front door and out

the back, or in the back door and out the front. I am looking at the new

landscape. The door is like the Arc de Triomphe––around it, through

it, comes the air of possibility. When I crossed the threshold, I left

nothing behind. There is no wall between the past and future. This wasn’t a spiritual

journey. Nor was it a temporal journey. It was a door I have walked through.

Everything begins here. There’s a weight to it. It’s as if I’ve built my

own concrete house and then walked through it––in the front door and out

the back, or in the back door and out the front. I am looking at the new

landscape. The door is like the Arc de Triomphe––around it, through

it, comes the air of possibility. When I crossed the threshold, I left

nothing behind. There is no wall between the past and future.

There’s nothing sentimental

about actual returns. Nostalgia is only a place in the mind. When you literally

touch the past, it disintegrates. It will not let you stay there; and because

you can’t stay there, it propels you into the future––it is a door.

Childhood has nothing to do with smallness. As a child, I was

a genie, I created the biggest world in the world. When childhood, the

biggest dream of all, reverts back to reality, it vanishes, turns into

a door. She smiles.

We are smiling at each other.

We are seeing each other through the mirrors of our past. She is

the young woman I knew. I am the child who liked to draw, whom she

left in a cabin at night, in the light of a kerosene lamp. She is

the woman with white hair, who prayed to the other Mary day and night.

***

She was supposed to receive the award with which Yad Vashem (in Israel)

honors gentiles who helped Jews during the war. The letter she had received

confirmed it. I have written to Yad Vashem again, their bureaucracy is

like any other, I have told them, she is eighty-five. It would mean

a great deal to her.

***

“Can you tell me what flowers we had

there? I need their names, for my writing, and I don’t remember.”

“Flowers?”

“Yes.”

“Well, you see it

was so long ago. We had roses––”

“No, I mean in the

fields.”

“In the fields?”

“Yes.”

“In the fields we

had habri, and maki (poppies). We had chamomile flowers,

and those small tiny ones . . . niezapominayki (forget-me-nots).”

***

Unless you return to the past and

touch it, you stand in place. The fear of returning is the fear of the

future. My God, what will happen to me, I had thought. Going back is different

from remembering. Remembering is gilded, going back is facing impoverishment.

The nourishment of the dream disintegrates; one has to re-experience hunger,

to proceed. In order to survive death, we must die.

I am no longer here, says

Szumska, the serious look of a child on her face. When I was a child, she

was not my mother. When I was a child we were spirits together. Majka is

mother to the child Szumska. Maria Szumska was never just a mother, her

soul has a revolutionary bent.

She smiles.

The secret between us is

as deep as the lake she took us to when I was eight.

1. My parents have died

since this was first written.

2. Jacek has also died.

3. Remnants of the

Last Jews of Poland by Malgorzata Niezabitowska, 1986.

4. Haby, or Habry,

or Chabry in Polish, is the title of my forthcoming book of poems

and a story.

Copyright © 1991 by Helen Degen Cohen.

This memoir first appeared in The House on Via Gombito:

Writing by North American Women Abroad, edited by Madelon Sprengnether

and C. W. Truesdale. Minneapolis, MN: New Rivers Press, 1991.

The photographs of Maria Szumska are in the private possession

of the author and used with permission.

Return to beginning.

|