Poetry Porch 3: Poetics

Of the Sonnet and

Paradoxical Beauties:An interview with Rafael Campo

In October 1997, Joyce Wilson and Rafael Campo participated in this interview, which took place through email. Rafael Campo is a practicing physician and lecturer at Harvard Medical School. He has published two volumes of poetry, The Other Man Was Me, Arte Publico Press, 1994, and What the Body Told, Duke University Press, 1996, and a book of essays, The Poetry of Healing, W. W. Norton, 1997.

JW: At a reading last winter, at Boston University I believe, we spoke briefly afterward, and I remember your reference to some of your poems as ER poems (referring to the popular television show based on dramatized emergency room situations). This comment led me to expect that I would find an apparent difference in your work, from first book to second, in which the first contained a set of narratives based on your experience as a medical physician, and the second moved on to meet the challenges of the poetic craft, concentrating on form after the earlier were based more on content.

When I read your poems, I didnít find the clear delineation of efforts that I anticipated at all. It was obvious from the beginning that you have been experimenting with the sonnet form all along. Am I correct in concluding that the sonnet is the most represented form in both books? Many of the poems in the first book appear to me to be narratives in 14 lines that follow loose rhyme schemes. And then some are 16 lines, with an abba, etc. rhyme scheme. One ends with a 13th line. Why the sonnet form?

RC: Yes, I am fascinated by the sonnet, and the form is of crucial importance in both books. The reasons for my affinity to the sonnet are manifold. First, the sonnet has always stood at the imagined intersection of the romance languages and English (given its history) ---as a bilingual writer, Iíve always longed for ways to make English sound somehow like Spanish, to re-create the musicality of my first language in my adopted tongue. Second, I find the erotics of the form terribly compelling---as a gay writer, I relish the paradox of claiming this traditional medium of the love song as my own, playing by the rules and yet crossing boundaries, and thus demonstrating that the rhythms and pleasures of lovemaking truly are universal. Lastly, I would say of the sonnet that no other way of writing poetry so completely mirrors what I discover in my patients occupying of their physical bodies--the undercurrent of iambs in the beating heart and breathing lungs, the gorgeousness of rhyme akin to dressing up the body in layers of clothes, the replication of the same patterns across centuries a kind of literary genetics.

JW: Which poems are your ER poems? Were they a departure from your other poems? Do they draw a more enthusiastic audience than those poems that are more technical? Or were you working on some less apparent formal aspect with them?

RC: When I spoke of my "ER poems," I was referring to the long sequence of deconstructed sonnets called "Ten Patients, and Another" that forms the heart of my second book What the Body Told. They are a departure from my other work in several respects, in that they attempt to return what I sometimes think of as the appropriated narrative of the medical history back to the rightful owner, the suffering human being. My intention was to de-glamorize human suffering as displayed on such unrealistic (despite all the hype about their "realism") dramatizations as the TV shows "ER" and "Chicago Hope"---to tell the truth, against the current of the sonnetís part-artificial beauty too, against also the medical professionís constant digesting and revising of the narratives of human suffering. I tried to turn medical terminology on its head, to make it accommodate the truths of the people it supposedly serves; I tried to turn poetry on its head, too, by making it address the squalid, the ugly violence, the powerlessness, the shame. What I hope I produced was some kind of testimony to the fundamental dignity of all humanity, and, yes, the paradoxical beauty of need.

JW: When youíre writing, do you know the first jottings will be a sonnet before you begin to put words on the page? Does the form take shape as an application from the outside? Or do you work from the inside out, the way Michelangelo described seeing the form as it already existed in a piece of marble? Do you revise a lot?

RC: I compose most of the early drafts of my poems in the part of my brain that is stimulated but yet not often given the opportunity of full expression when Iím at work in the hospital---writing poetry is a process that parallels my efforts to ameliorate suffering. When I finally have enough time to sit at my desk to write in my journals, or with the clear intent to write a new poem, I find that the words have already been molded and shaped by my clinical work, so that what I write seems finished to me. Of course, I donít deprive myself of the pleasure of going back to this work, which I often do revise later, as thereís always more experience to bring to bear on whatever it is Iíve tried to engage---often, Iíve dipped back in to my poetry library to re-read a poet whose work intersects what Iím trying to do. Reading the poetry of others, whether in last weekís literary journals or last centuryís anthologies, is a critical part of the final polishing process.

JW: "Subverting forms" is a standard strategy artists have been known to take. Have you intentionally studied forms to subvert them? Have you found this successful? Has subversion been part of your approach?

RC: I donít think of what Iím doing as really "subverting" form---but, in the tradition of Shakespeare or Donne, and in our era, Marilyn Hacker and Julia Alvarez, instead challenging the form to make room for a diversity of experiences and resonating voices. I love the idea of pressing against the walls of the narrow room of the sonnet form until my (intellectual) muscles ache, and I take great pleasure at the same time in obeying the rules that the form absolutely requires. I find that the friction creates a kind of heat that courses through the poems that result. Whether itís a stiff New England obstacle (encountered during my college days at Amherst) to the Cuban histrionic sentimentalism about family and romantic love (inherited from my immigrant father), the poem that results, though perhaps not "perfect" according to eitherís set of definitions, is something new, something American, something that defies categorization and demands to be heard out. Ultimately, I hope, the poem I write is a medium for exploring empathy, for uncovering what is universal in the most diverse of life experiences.

JW: In your book of essays, The Poetry of Healing, you construct a chapter as an answer to the question from many close to you, "Why do you write formal poetry?" Then you construct an answer based on autobiographical experiences, a way of "deliberately applying boundaries and barbed wire to these new aspects of myself." Are these autobiographical structural efforts establishing a "new formalism"?

RC: The notion of a "new formalism" strikes me as avoiding the main issue. To create another category seems to be an expedient way to dismiss, or to cordon off, or to refuse a dialogue between a new and growing body of work and the larger one to which all poets must remain connected. Similarly, I think the category of "new formalism" creates a distracting division between contemporary poets who choose to write in form and those who do not---while anyone whose passion is poetry knows that any kind of new writing must take its place alongside what has gone before it and what is going on around it. When I teach poetry to medical students and residents, our focus is on the immersion in anotherís voice, on how the language enters us viscerally, on witnessing the poemís unique capacity for creating empathy---regardless of the particular "camp" to which the poets we read may assign themselves (or be assigned by others). Honestly, there are political struggles of far greater importance in which Iíd rather involve myself, than the oftentimes small-minded debates of new formalism versus old, or free verse versus formalism! Now, all that is not to deny the emergence of a group of gifted poets whose lived experience is exerting new and wonderful pressures on received forms---more proof of the vitality and capaciousness of these same forms than an argument for a whole new category of writing poetry.

JW: Later in that essay, you write about the realization that "the very act of living itself was the source of energy to write poems." Would you say that the motive of "life force" is the primary element in aspiring the writing of poetry today?

RC: While I do certainly hear the rhythms of the bodyís heartbeat or breathing in iambic poetry, or of walking in syllabic verse, I have to cautious about what might be understood too reductively in this regard. Poetry is written for so many reasons, is prompted out of so many experiences, and is read from so many different vantage points, that it would be difficult to defend the notion of "a life force" as being the primary motivator of so much activity! Certainly, it would be hubris to suggest, for example, that by extension writing poetry could somehow cure cancer or AIDS. Yet in my own particular work as a doctor and poet, I do encounter areas of overlap that make me believe that the origins of poetry and our attraction to it run very deep within us. In the very act of authorship, I have seen the reestablishment of imaginative control of bodily processes gone awry; in the translocating metaphor, the movement of healing, or dying, is suggested. Poetry is the lifeblood of community; by fostering empathic connections among people, it may indeed remind each of us of our own ongoing process of being alive, of how and why we live.

JW: As a medical student, did you read Arrowsmith? What are your favorite books or poetry collections in relation to the medical career?

RC: My favorites would be Marilyn Hackerís Winter Numbers and Selected Poems, both from W. W. Norton; Thom Gunnís The Man with Night Sweats and Collected Poems, from FSG; Gary Fisherís Gary in Your Pocket, a collection of poetry and journal writing edited by Eve Sedgwick for Duke University Press; Mark Dotyís My Alexandria and Heavenís Coast; Alan Shapiroís stunning memoir Vigil, about caring for his sister as she dies of breast cancer; M. Wyrebeckís Be Properly Scared, recently published by Four Ways Books; the collected poems of William Carlos Williams, from New Directions; The Knot, by fellow physician-poet Alice Jones, from Alice James Books.

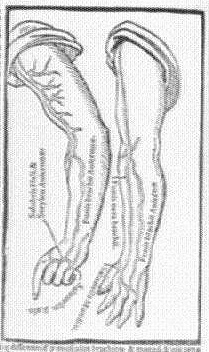

"Arteries of the arms and legs," woodcut by Jacopo Berengario da Carpi. 1460-1530.

Return to the Archive 1998 contents page.

Return to the Poetry Porch home page.