The Grolier Poetry Book Shop

A Bookstore for Poets and Lovers of Verse

Notes from Academe by Lawrence Biemiller

From THE CHRONICLE OF HIGHER EDUCATION, OPINION, SEPTEMBER

6, 1996

(Copyright 1996, The Chronicle of Higher Education.

Posted with permission on The Poetry Porch. This article may not be published,

reposted, or distributed without permission from The Chronicle).

Cambridge, Massachusetts. In 1974, Louisa Solano was fired from

her job at a local bookstore—"for my belligerent attitude," she

says with a mischievous smile. Shortly afterward, the executor of Gordon

Cairnie’s estate asked her to take over Mr. Cairnie’s one-room bookshop

on Plympton Street. It was called the Grolier, and it shared a block with

the most bohemian of Harvard University’s residential colleges, Adams House.

The Grolier has been open 47 years, and it had an enviable reputation as

a meeting place for writers, especially poets.

What it did not have, Ms. Solano knew, was a marketable inventory, or

a respectable credit rating, or a lot of customers. "Gordon was famous

for his post-card correspondence with everybody," she says. "He

never sold books, he never paid bills, he just wrote post cards. And he

was cantankerous. People who came into the store would be insulted."

Ms. Solano, in fact, had seen this happen again and again—she had been

going to the Grolier regularly since she was 15. "I used to hang out

there, straighten up the piles, dust things. I was very, very quiet and

never joined the conversation."

By the time

Mr. Cairnie died, Ms. Solano had been working in other bookstores for years

and had earned a bachelor’s degree from Boston University. She managed

to get a bank loan, co-signed by friends, and a three-month lease on the

shop. She junked most of the secondhand volumes, got rid of stacks of old

magazines, and decided to concentrate on selling poetry: "Most of

the customers in the ‘70s were poets, and most of the books that were in

saleable condition were poetry."

By the time

Mr. Cairnie died, Ms. Solano had been working in other bookstores for years

and had earned a bachelor’s degree from Boston University. She managed

to get a bank loan, co-signed by friends, and a three-month lease on the

shop. She junked most of the secondhand volumes, got rid of stacks of old

magazines, and decided to concentrate on selling poetry: "Most of

the customers in the ‘70s were poets, and most of the books that were in

saleable condition were poetry."

"Everybody thought I’d be gone in a day," she says. Twenty-two

years later, the Grolier Poetry Book Shop has 14,468 titles in stock and

legions of loyal fans, some of whom visit in person and some of whom send

in their orders, from as far away as Japan. Ms. Solano believes it is the

only store of its kind in the United States. "The other all-poetry

bookstores are either secondhand or first-edition," she says. "I

think we’re the only off-the-street, open-to-the-public, in-print poetry

bookstore."

Actually, it’s that and much more. The Grolier sponsors poetry readings

at Adams House every Tuesday night during the academic year, and book signings

every Saturday afternoon. It also sponsors its own poetry competition,

the Grolier Prize, "for people who don’t have previous publications—to

give somebody an opportunity," Ms. Solano says.

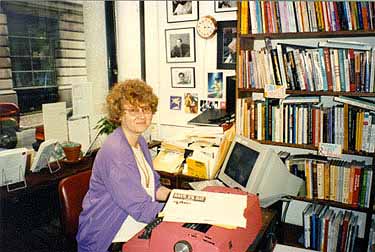

Ms. Solano herself serves as a one-woman information exchange for her

customers, poets and readers alike. She recommends books to students and

other new readers, suggests workshops and publishers to aspiring writers,

passes along new gossip and old, even sets customers up on dates. (She

never sets up one poet with another, though.) She dispenses advice to novices

("A lot of people have never thought of reading aloud") and to

callers who want to console themselves with poems after a loved one has

died (she recommends Tennyson’s "In Memoriam"). The two things

she won’t do, she says, are help people pick verses to read at weddings

and help those whose questions are primarily commercial—for instance, a

publishing-house editor who wants to know what new poems to include in

an anthology. "I charge for consulting," she says.

As bookstores go, the 404-square-foot Grolier is a marvelous, cluttered anachronism.

A plate-glass window overlooks Plympton street, and shelves climb all the

way up the high walls. A big, square table in the center of the store is

stacked with books—Robert Pinsky’s new volume, The Figured Wheel,

sits near a Collected Poems of William Butler Yeats and an anthology

called In Time: Women’s Poetry From Prison, which has only 13 numbers

pages. Beside these are audio tapes, including one called Becoming a

More Productive Writer and another that features Maya Angelou reading

"The Inaugural Poem." There are dozens of journals, and a poetry

cookbook called Written With a Spoon, and a wonderful collection

called Poetry in Motion: 100 Poems from the Subways and Buses, the

copyright to which is held jointly by the Poetry Society of America and

New York’s Metropolitan Transit Authority.

Books by American poets are arranged alphabetically along the back wall,

although half a shelf of overflow F’s is stacked in front of the E’s, blocking

both John Engels and Daniel Mark Epstein. The computer and the telephone

crowd into a paper-strewn niche by the end of the alphabet, complicating

access to everyone from R through Z. The left wall displays books arranged

by category—African American, Chinese, Cowboy, Epics, Gay and Lesbian,

Greek and Latin, Irish, and so forth. "The philosophy I started from

was to broaden the outreach of this store," says Ms. Solano. "Having

been around here so long, I was well aware of how narrow the clientele

was."

The store is open daily from noon to 6:30—except Sunday, which is Ms.

Solano’s day off. Otherwise she arrives around 10, along with Jessie, her

dog. She uses mornings for things she can’t get to when the store is open—like

uninterrupted phone conversations. At 11:30 or so she walks around the

corner for a bagel, which she eats in the Adams House lobby. The first

customer arrives shortly after she unlocks the door—today it’s a graduate

student in education who wants to know where he can find open poetry readings,

and whether Ms. Solano can suggest a free-lance critic he could pay "to

read my stuff and rip it apart."

Their conversation is interrupted by a call from someone who complains

about book prices for 10 minutes and ends up ordering an $8 volume. This

is just the kind of complaint that steams Ms. Solano. "People come

in with custom-made T-shirts that probably cost $15 or $20, yet they complain

abut the cost of a book someone’s been working on for years," she

says. "Most of these books cost less than a hamburger on Holyoke Street."

She speaks fondly of other customers, however. ‘There was an engineer

for NASA who walked into the store after reading about it. He said, ‘Teach

me something about poetry.’ Now he has one of the largest collections in

the country. Another customer sent $600 every other month and told me to

send small-press books to various schools where his children had gone.

I met him only once, at the very beginning, but he helped keep the store

alive for years, and helped pay the small-press bills."

A slow day at the Grolier may bring in only 25 people; a busy day, 100.

Ms. Solano runs the shop more or less single-handedly—selling poetry isn’t

especially profitable, even if your landlord is Harvard and you get a break

on your rent for operating a cultural resource. This summer, when Ms. Solano

had to take two months off to recover from surgery, customers kept the

store open for her.

When she’s not answering questions or ringing up a sale, she packs up

books she’s mailing out, or phones customers to let them know that books

they’ve ordered have arrived. She hardly seems belligerent. She laughs

as she tells stories about poets she’s met, and every few minutes she recommends

another book: "Have you read Timothy Liu? He’s an ex-Mormon poet.

He was one of the winners of our poetry prize." Mr. Liu teaches at

Cornell College; his latest book, which she pulls from the L’s, is called

Burnt Offerings. She describes Martín Espada, who teaches

at the University of Massachusetts at Amherst, as "an ex-lawyer and

a terrific reader." His new book, Imagine the Angels of Bread,

joins Mr. Liu’s on a visitor’s to-buy pile.

Ms. Solano is not a poet herself. She says she’s partial to Jane Austen,

whose novels she rereads every year, and to Chaucer. But she seems familiar

with every book anyone asks about in the course of the afternoon—indeed,

she almost seems familiar with every poem. "I read poetry for the

image and the sound," she says. "I don’t find the thoughts and

the experiences all that unique, but I love language." There can be

not doubt of that. She has 14,468 titles as proof.

(Photograph courtesy of Grolier Poetry Book Shop.)

Return to the Poetry Porch homepage.

By the time

Mr. Cairnie died, Ms. Solano had been working in other bookstores for years

and had earned a bachelor’s degree from Boston University. She managed

to get a bank loan, co-signed by friends, and a three-month lease on the

shop. She junked most of the secondhand volumes, got rid of stacks of old

magazines, and decided to concentrate on selling poetry: "Most of

the customers in the ‘70s were poets, and most of the books that were in

saleable condition were poetry."

By the time

Mr. Cairnie died, Ms. Solano had been working in other bookstores for years

and had earned a bachelor’s degree from Boston University. She managed

to get a bank loan, co-signed by friends, and a three-month lease on the

shop. She junked most of the secondhand volumes, got rid of stacks of old

magazines, and decided to concentrate on selling poetry: "Most of

the customers in the ‘70s were poets, and most of the books that were in

saleable condition were poetry."